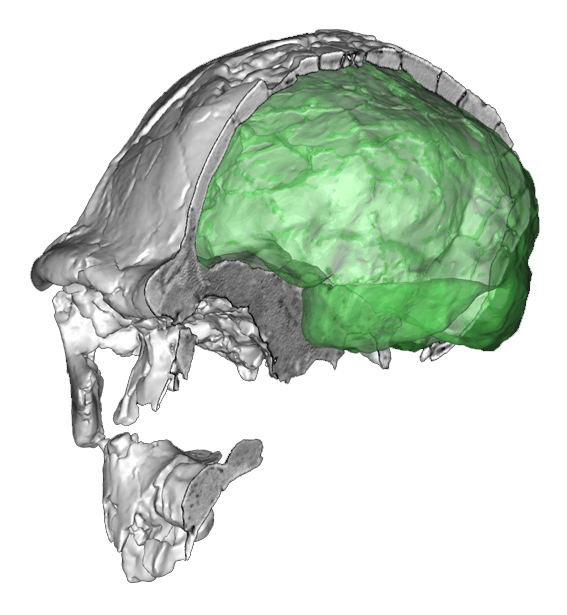

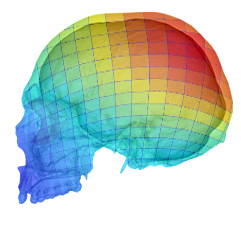

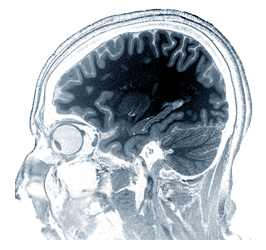

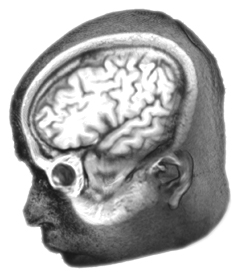

This week, with a team coordinated by Michael Masters (Montana Tech), we have published a correlation analysis to evaluate the relationships between eye, orbit, and brain, in adult modern humans. As already evidenced in other studies in anthropology and primatology, the correlation between eye size and orbit size is very modest. Therefore, the orbit is really a poor predictor of the eye morphology, at both evolutionary and species-specific level. There is also a minor size correlation between the eye and the occipital cortical areas, probably because of their shared visual functions. However, there is also a similar (and even higher) correlation between eye and frontal lobe. In this case there is a structural issue: the frontal lobes lie just above the orbits, generating a spatial interaction between facial and neurocranial elements. Within hominids, this spatial proximity between prefrontal cortex and eyes is generally observed only in modern humans and Neandertals. These two taxa, possibly because of such vertical constraint, enlarged their frontal lobes mainly laterally. These correlations between soft and hard tissues, when dealing with inter-specific trends, can be useful to make inferences on brain proportions based on osteological evidence, providing an heuristic tool for indirect paleoneurology.

This week, with a team coordinated by Michael Masters (Montana Tech), we have published a correlation analysis to evaluate the relationships between eye, orbit, and brain, in adult modern humans. As already evidenced in other studies in anthropology and primatology, the correlation between eye size and orbit size is very modest. Therefore, the orbit is really a poor predictor of the eye morphology, at both evolutionary and species-specific level. There is also a minor size correlation between the eye and the occipital cortical areas, probably because of their shared visual functions. However, there is also a similar (and even higher) correlation between eye and frontal lobe. In this case there is a structural issue: the frontal lobes lie just above the orbits, generating a spatial interaction between facial and neurocranial elements. Within hominids, this spatial proximity between prefrontal cortex and eyes is generally observed only in modern humans and Neandertals. These two taxa, possibly because of such vertical constraint, enlarged their frontal lobes mainly laterally. These correlations between soft and hard tissues, when dealing with inter-specific trends, can be useful to make inferences on brain proportions based on osteological evidence, providing an heuristic tool for indirect paleoneurology.

So, back to modern human evolution, the situation of the eye was pretty difficult: large eye (due to brain size increase), small orbit (due to facial reduction), upper constraints (the frontal lobes right on the orbital roof), posterior constraints (larger and closer temporal lobes). And, in industrial Countries we can also add more fat between eye and bone. Hard times for the eyeballs, forced to minor deformations blurring images on the retinal screen: myopia. Luckily for us crossing the 40s, the brain stops growing, but the face does not: it grows bigger, giving more space to the eye, which can enjoy a more comfortable environment year by year.