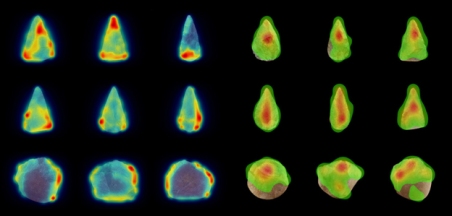

This week, I have published a comprehensive perspective review on cognitive archaeology in the Journal of Comparative Neurology. The article introduces fields bridging prehistory and neuroscience, like paleoneurology and neuroarchaeology. Successively, the relationship between fossils and cognition is discussed following the principles of cognitive archaeology, and the application of psychological models to those behaviors relevant to human evolution. It is important to consider that evolution is based on multiple independent lineages, which make linear, gradual, and progressive changes unlikely. Therefore, the traditional view considering fossil species as “something less” than modern human standards, might be seriously biased. Each species has a distinct combination of mental abilities, and this is probably true also when dealing with extinct taxa and their mind: fossil hominids might have had cognitive skills that we have lost, or never evolved. The cognitive landscape can be, in this sense, influenced by differences in quantity (increasing/decreasing specific skills) and quality (presence/absence of specific skills). In this sense, the simple presence of a specific behavior in the archaeological record is not sufficient to reveal the expression of common cognitive patterns. The frequency of the behavior is crucial, because of the importance of distinguishing occasional vs. habitual responses and adaptations. The complexity of the behavior must also be considered, to avoid generalizations that can hide consistent cognitive changes.

The review then deepens into the fronto-parietal system, working memory, visuospatial cognition, and attention. Following perspectives on embodiment, the importance of the body is discussed in terms of consciousness and self. Haptic, psychomotor, and kinesthetic abilities have mechanical and cognitive aspects, with blurred boundaries with many other broad and narrow skills. At present, we still miss proper conceptual and psychometric tools to investigate their actual roles and influences. Social and technological aspects are also further introduced. Attention, as a cognitive limiting factor, is then particularly discussed, taking into consideration that modern human has a social and technological system that suggests recent evolutionary enhancements in executive, top-down, and focused attentional skills. Many of our cognitive and cultural achievements are probably due to the fact that our attention is intentional, sustained, and conscious.

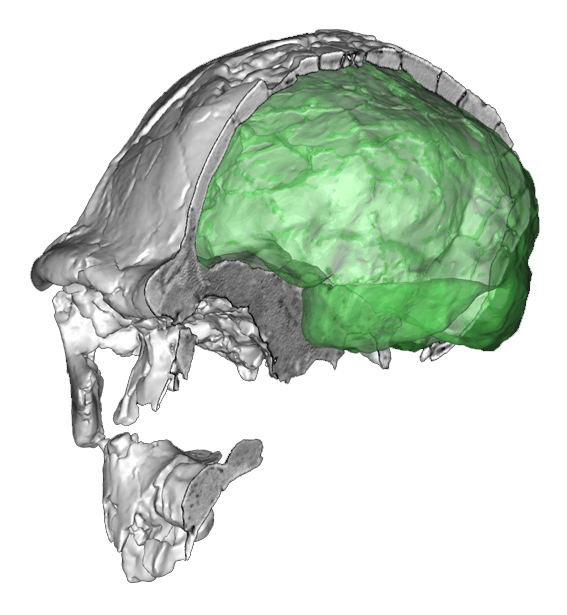

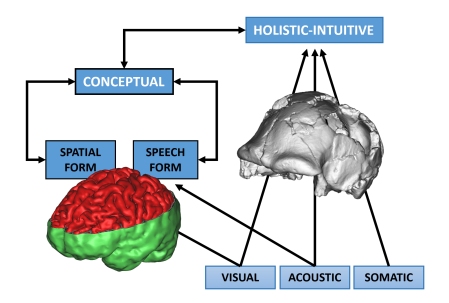

Finally, the role of the parietal cortex in the narrative of the self is presented. The precuneus, which is much larger in Homo sapiens when compared with other primates and, probably, with extinct hominids, is interpreted as a “beamer” of our storyline, integrating body and visual imaging. The outstanding imaging capacity of our species has, anyway, a drawback: an out-of-control mind wandering through past memories, future expectations, and ruminations, leading to that ontological suffering described by multiple philosophical traditions. If this vulnerability is due to a mismatch between attentional and visual skills, competing for the same neural and cognitive resources, such suffering must be interpreted as a human universal, following the principles of human ethology. Subsequently, I introduce the subsystem model of John Teasdale, employed in Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) and based on two different forms of reasoning: holistic intuitive (based on perception) and conceptual (based on phonological and imaging resources). The former is largely developed on on-line somatic and attentional factors, while the latter is based on off-line information, working memory, and the default network. We can hence wonder whether different hominids might have relied on distinct combinations of the two subsystems.

The review ends with a call for experimental and quantitative methods in cognitive archaeology. Experimental psychology can supply, in this sense, efficient tools and perspectives. Sometimes, experimental approaches are criticized in cognitive archaeology because of the employment of “modern minds” to make experiments, forgetting that, usually, apes are used as models for human evolution, macaques are used as models for the human brain, and mice and worms are used as models for the human medicine. Science works with models. In this case, a human (H. sapiens) is used as a model for other humans. Not that bad! A second common criticisms deal with the fact that theories and hypotheses in archaeology cannot be proven. This is true, as it is for any other field of science. Selection of hypotheses is based on available data, in physics, ecology, or molecular biology. That’s how science works. As a final remark, the review stresses the importance of somatic, social, and technological elements when investigating cognition, in particular when dealing with a human primate.