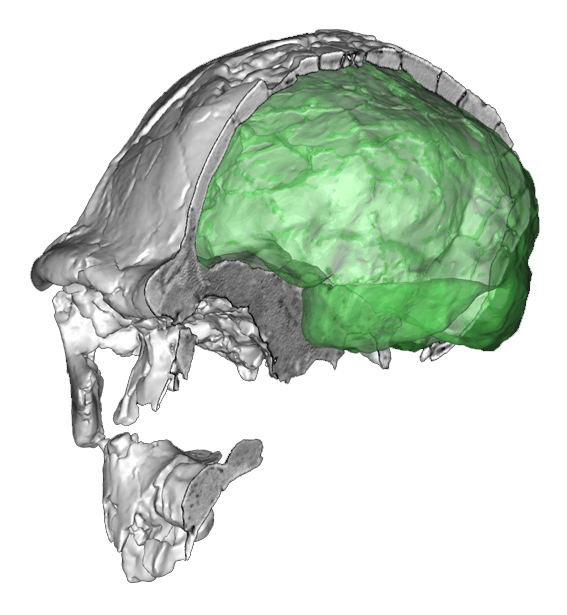

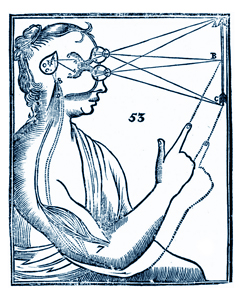

Together with Marina Lozano (IPHES), this week we have published a JASs Forum on a speculative hypothesis concerning the use of the mouth in support to praxis and handling in Neandertals and their ancestors, as evidenced through the analysis of their dental marks. This behaviour, very common in Homo neanderthalensis and Homo heidelbergensis, is not so frequent in modern hunter-gatherer. According to the theory of extended mind, cognition is the result of the interaction between brain and environment as mediated by the experience of the body. The main “ports” of such interface are the eye (input, from the world to the brain) and the hand (output, from the brain to the world). Modern human brain displays a peculiar dilation of the deep parietal areas, which are particularly involved in visuo-spatial integration, which includes the management of the eye-hand system, the integration with memory, and the integration with frontal executive functions. Hence, we suggest that the necessity of a further additional element (the mouth) may be necessary when the standard anatomical elements are not sufficient to integrate the body relationships with the cultural complexity. A mismatch between the biological substrate (neural system/body interface) and cultural substrate (complex tools and behaviours) could have been the backstage of a risky involvement: the mouth as integrative body support. The investment is not safe, considering the importance of the mouth in different and relevant functions, and it sounds like an extreme solution. Neandertals do not show a similar enlargement of the parietal areas, when compared with Homo sapiens. Although we ignore the exact relationship between brain form and function, the fact that these areas are crucial for visuo-spatial integration is, at least, intriguing. Needless to say, a possible mismatch between neural and cultural systems in Neandertals should not be interpreted as an “intermediate” condition between archaic and modern forms, but else as a lack of proper coordination associated, as far as we know, with an evolutionary blind alley.

Together with Marina Lozano (IPHES), this week we have published a JASs Forum on a speculative hypothesis concerning the use of the mouth in support to praxis and handling in Neandertals and their ancestors, as evidenced through the analysis of their dental marks. This behaviour, very common in Homo neanderthalensis and Homo heidelbergensis, is not so frequent in modern hunter-gatherer. According to the theory of extended mind, cognition is the result of the interaction between brain and environment as mediated by the experience of the body. The main “ports” of such interface are the eye (input, from the world to the brain) and the hand (output, from the brain to the world). Modern human brain displays a peculiar dilation of the deep parietal areas, which are particularly involved in visuo-spatial integration, which includes the management of the eye-hand system, the integration with memory, and the integration with frontal executive functions. Hence, we suggest that the necessity of a further additional element (the mouth) may be necessary when the standard anatomical elements are not sufficient to integrate the body relationships with the cultural complexity. A mismatch between the biological substrate (neural system/body interface) and cultural substrate (complex tools and behaviours) could have been the backstage of a risky involvement: the mouth as integrative body support. The investment is not safe, considering the importance of the mouth in different and relevant functions, and it sounds like an extreme solution. Neandertals do not show a similar enlargement of the parietal areas, when compared with Homo sapiens. Although we ignore the exact relationship between brain form and function, the fact that these areas are crucial for visuo-spatial integration is, at least, intriguing. Needless to say, a possible mismatch between neural and cultural systems in Neandertals should not be interpreted as an “intermediate” condition between archaic and modern forms, but else as a lack of proper coordination associated, as far as we know, with an evolutionary blind alley.

The hypothesis has been commented by Lambros Malafouris, Marco Langbroek, Thomas Wynn, Fred Coolidge, and Manuel Martin-Loeches. Next issues to be considered: details of the hand anatomy and hand management, early modern humans associated with Mousterian tools, and functional behaviours in those modern populations that use mouth and teeth for praxis. Hypotheses in cognitive archaeology are necessarily speculative. But we can try nonetheless to supply multidisciplinary evidence to integrate paleoneurological and archaeological data, providing at least a logical framework. In this case the next step is clear: to evaluate further this hypothesis we have to investigate more visuo-spatial behaviours in these extinct forms.

[You can download here the whole forum]