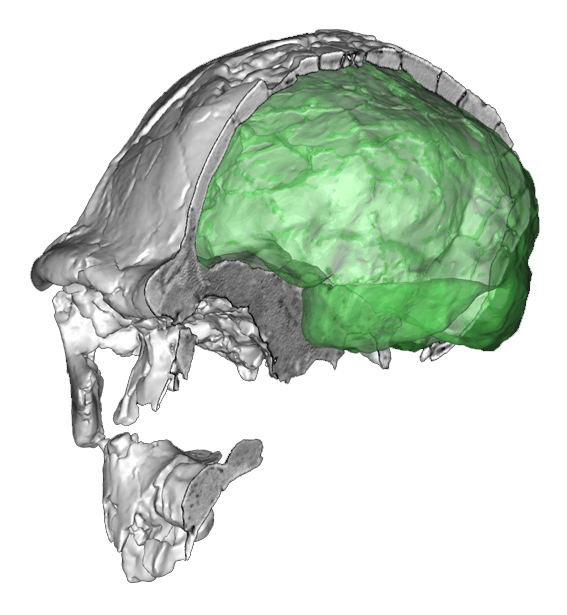

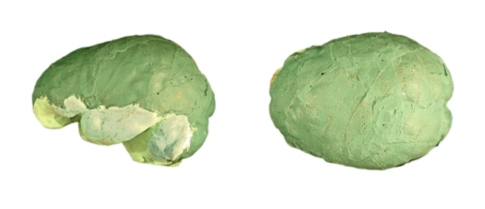

This week we have published a paleoneurological study of the specimen DAN5/P1, found in Ethiopia (Gona) and dated to 1.5 million years. According to the cranial features, the skull can be assigned to Homo ergaster/erectus. Nonetheless, the cranial capacity is very small, estimated as 598 cc. Ralph Holloway reconstructed an endocast based on the available bones. The endocranial morphology suggests brain proportions that are very similar to australopiths and to specimens generally assigned to the elusive species H. habilis, like KNM-ER 1805 and KNM-ER 1813. Most of the brain variation in these early and archaic hominids is apparently due to size, and patent differences between genera or species are difficult to establish. This can mean that most brain diversity within and between these taxa is only due to size changes and shared allometric patterns. Or that the fossil record is too scanty to provide robust statistical information. Or that endocasts, although representing the most valuable source of information on the brain of extinct species, cannot show subtle cortical details. Either way, we can probably say that macroscopic brain differences between these early and archaic species (beyond mean brain size) are absent or at least subtle. Of course, the absence of (anatomically or statistically) consistent macroscopic difference does not exclude the possibility of internal changes, associated with cell and tissue organization, connections, metabolisms, or neurotransmitters. The difficulties in detecting specific brain differences in these early humans remark the uncertainties on the phylogenetic origin of our genus, as mentioned in this recent article on human paleoneurology. Here’s another perspective review, pointing at the possibilities and limitations of the field.

Tag: Homo erectus

Gona, Ethiopia

After an accurate digital reconstruction, we have now published a comprehensive metric analysis of two crucial fossils from Gona, Ethiopia, namely DAN5/P1 (1.5 million years) and BSN12/P1 (1.3 million years). These fossils (here the original description) display traits which are shared by Homo erectus and other early human species. DAN5 shows a general affinity with the Dmanisi fossils, as well as with KNM-ER 1813. Such similarity is probably due to the fact that, in these early humans, a large part of the cranial morphological variation is allometric, and therefore scarcely informative in terms of phylogenetic differences. Indeed, these skulls have a very small overall size. Other features (like the midline keeling or the angular torus) support an interpretation of these specimens as early African H. erectus. The analysis evidences an evolutionary trend in brain expansion, but no patent effects of sexual dimorphism. The study was coordinated by Karen Baab. Here a Share Link for 50 days’ free access to the article, valid until January 27th, 2022.

Ileret

I had missed this amazing study (2018) from Neubauer and colleagues on the skull and endocast KNM-ER 42700 from Ileret, Kenya, with a chronology of 1.5 million years. They performed a set of reconstructions for the skull and endocast, and compared these figures within the diversity of early hominids. Their results are quite convincing, and confirm that the specimen is definitely out of the range of variation of adult Homo erectus. Overall, the endocast is somehow similar to the endocast of KNM-ER1470 (H. rudolfensis). However, its morphology also lies midway along an ontogenetic trajectory going from Mojokerto to adult H. erectus. So, the taxonomy of KNM-ER 42700 can be uncertain, but the most likely explanation is a H. ergaster/erectus of a young age, much younger that predicted on the basis of other cranial features. Taking into consideration the approach based on multiple reconstructions, the multivariate shape toolkit, and the disclosure of the ontogenetic trajectory of H. erectus, this paper is definitely a great paragon in paleoneurology. A review on metric endocranial variation in H. erectus was published some years ago here.

Buia

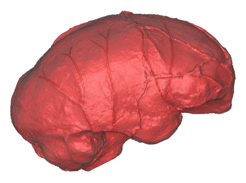

This week we publish a morphometric analysis of the endocranial anatomy of Buia, a skull found in Eritrea and dated to 1 million years. The cranial capacity is 995 cc. The endocast is extremely dolichocephalic: very long and narrow. Nonetheless, it shows all endocranial traits that are commonly described in “archaic humans“. The bulging occipital lobes and the vascular system resemble the Chinese specimens from Zhoukoudian. Its pronounced parietal bosses are due to a narrow cranial base and temporal areas, and not to a real enlargement of the parietal lobes. Actually, the cranial base in Buia is very narrow and flexed, and it may have influenced both the neurocranial and splanchnocranial proportions (bulging parietal surface and tall facial block). At present, there is no reason to exclude this specimen from the Homo ergaster/erectus group. The skull from Daka show a similar chronology and a similar geographic origin, although it displays much more brachycephalic proportions. If all these Afro-Asiatic archaic specimens belong to the same species, the variability is notable. It remains to be established whether the evolutionary roots of more derived taxa (like Homo heidelbergensis) can be traced back to these archaic populations, or else if Buia and Daka are still part of an undifferentiated phylogenetic group.

This week we publish a morphometric analysis of the endocranial anatomy of Buia, a skull found in Eritrea and dated to 1 million years. The cranial capacity is 995 cc. The endocast is extremely dolichocephalic: very long and narrow. Nonetheless, it shows all endocranial traits that are commonly described in “archaic humans“. The bulging occipital lobes and the vascular system resemble the Chinese specimens from Zhoukoudian. Its pronounced parietal bosses are due to a narrow cranial base and temporal areas, and not to a real enlargement of the parietal lobes. Actually, the cranial base in Buia is very narrow and flexed, and it may have influenced both the neurocranial and splanchnocranial proportions (bulging parietal surface and tall facial block). At present, there is no reason to exclude this specimen from the Homo ergaster/erectus group. The skull from Daka show a similar chronology and a similar geographic origin, although it displays much more brachycephalic proportions. If all these Afro-Asiatic archaic specimens belong to the same species, the variability is notable. It remains to be established whether the evolutionary roots of more derived taxa (like Homo heidelbergensis) can be traced back to these archaic populations, or else if Buia and Daka are still part of an undifferentiated phylogenetic group.

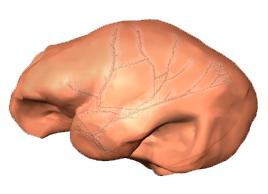

Homo erectus

Despite most than one century of studies, the taxonomic and phylogenetic status of Homo erectus is still largely debated. There is no agreement whether or not the African and Asian specimens belong to the same species, or on the meaning of the variation within the Asian group. The relevant influence of a shared allometric component, the large geographic and chronological span, the marked individual and idiosyncratic variability and (most important) the small sample size, hamper any definitive conclusion. Because of all these actual limits, we should seriously consider if our insistence in searching fixed and stable taxonomic certainties represents a necessary and useful effort. Because of these limits, probably paleoanthropology should rely on a different approach to taxonomy, more centred on the actual information available than on hypothetical and conceptual schemes. In the meanwhile, this week we publish a general review on Homo erectus paleoneurology. We describe the general morphology of the African and Asian Homo erectus endocasts, providing a quantitative perspective of their variation and variability by means of traditional endocranial metrics. As expected, no patent differences are evidenced among different geographic groups, being size and allometry the main source of variation. Of course, the absence of morphological differences in the endocasts does not necessarily means the absence of differences in brain organization, and it does not give information on the underlying taxonomical structure. The limits of the sample size are evident: a power analysis suggests that, beyond the issue of biological representativeness, for a simple variable like cranial capacity groups of at least 40 specimens would be necessary to deal with the statistical uncertainties! Nonetheless we can now state that, at least according to the current metric information, all the possible taxa included in the Homo erectus hypodigm share similar endocranial proportions.

Despite most than one century of studies, the taxonomic and phylogenetic status of Homo erectus is still largely debated. There is no agreement whether or not the African and Asian specimens belong to the same species, or on the meaning of the variation within the Asian group. The relevant influence of a shared allometric component, the large geographic and chronological span, the marked individual and idiosyncratic variability and (most important) the small sample size, hamper any definitive conclusion. Because of all these actual limits, we should seriously consider if our insistence in searching fixed and stable taxonomic certainties represents a necessary and useful effort. Because of these limits, probably paleoanthropology should rely on a different approach to taxonomy, more centred on the actual information available than on hypothetical and conceptual schemes. In the meanwhile, this week we publish a general review on Homo erectus paleoneurology. We describe the general morphology of the African and Asian Homo erectus endocasts, providing a quantitative perspective of their variation and variability by means of traditional endocranial metrics. As expected, no patent differences are evidenced among different geographic groups, being size and allometry the main source of variation. Of course, the absence of morphological differences in the endocasts does not necessarily means the absence of differences in brain organization, and it does not give information on the underlying taxonomical structure. The limits of the sample size are evident: a power analysis suggests that, beyond the issue of biological representativeness, for a simple variable like cranial capacity groups of at least 40 specimens would be necessary to deal with the statistical uncertainties! Nonetheless we can now state that, at least according to the current metric information, all the possible taxa included in the Homo erectus hypodigm share similar endocranial proportions.